Public Networks of Urban Access

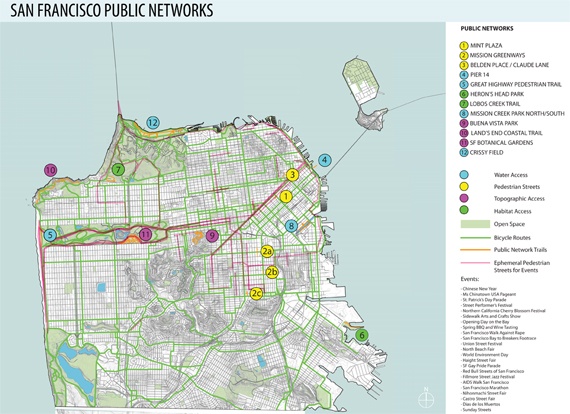

This past September, San Francisco held it’s annual “Architecture and the City Festival”. This year’s theme, “Investigating Urban Metabolisms,” asked participants to “… take an in-depth look at hidden and emergent systems that generate form, movement, growth and entropy in the city.” Taking part in the event, our office organized an exhibit titled “Public Networks of Urban Access,” which presented a variety of pedestrian open spaces developed in the city within the past 20 years, and analyzed the various emergent relationships that exist between them.

The exhibit interprets the festival’s theme of “Urban Metabolisms” by comparing the networks formed by these spaces to the various systems of the body and the roles they serve as parts of a unified whole. The aim of this process is to find creative ways to de-familiarize these sites so new interpretive value can be found – value which may guide future design strategies affecting the public space of the city. The detailed conditions, specific to each site, provide a broad basis for investigation, linking the various open spaces geographically, ecologically, socially, and historically.

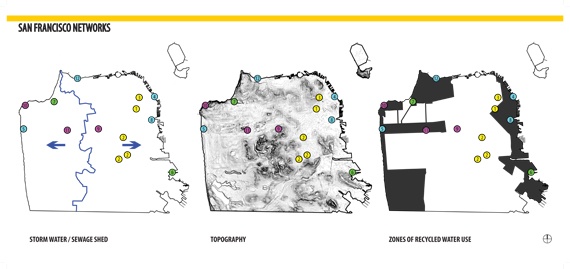

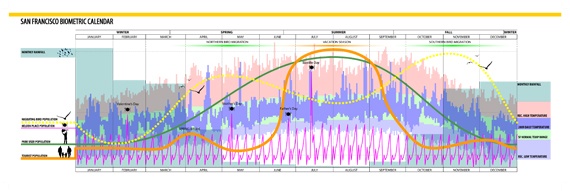

Pedestrian Networks function in the body of the City in a multiplicity of ways. They are designed to accommodate the human body, but also function environmentally and experientially. As a CIRCULATORY system, they get us from here to there; as a RENAL system, they filter water and air, improving our health and sustaining us; and as a NEURAL network they communicate the mutable natures of the urban environment – the haptic, visual, auditory and olfactory. This analogy provides us with the impetuous to explore the “comparative anatomy” of several recently improved San Francisco pedestrian networks and is meant to stimulate further exploration through estranging the familiar – revealing new perspective so that we can discover (experience) them anew.

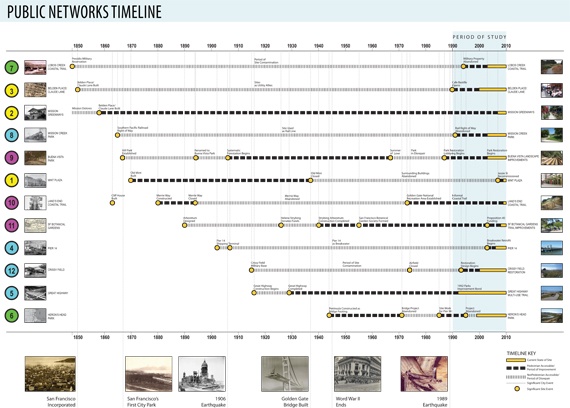

The projects presented, all of which provide access to wild landscapes, sensitive areas and waterfront, are intentionally diverse, and are categorized into one or more of the following: Topographic Access, Pedestrian Streets, Water Access, and Access to Sensitive Habitats. With each of the twelve projects represented we provided a field of comparative data, an abstract, communicating a brief history, the scope of the contemporary improvement, plan and sectional graphics, and an example of the designer’s vision or other experiential material – all meant to educate, awaken and inspire further exploration through self-guided visits to the individual projects.

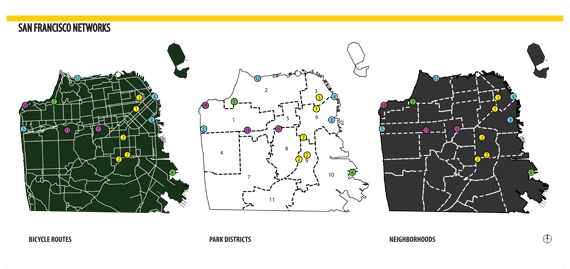

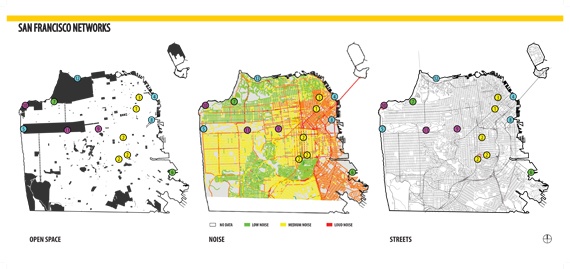

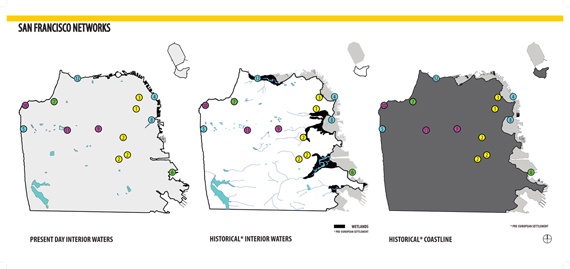

The projects are mapped onto various aspects of San Francisco to contextualize them in relation – to water, sound, neighborhoods, and other urban metabolisms and emergent systems- all play a role in how we know and understand these places.

The projects selected and showcased are a small selection of the emerging network of pedestrian access and pedestrian-centered environments that have been designed, built and improved upon in the last two decades in San Francisco. The emerging pedestrian network is one that highlights the changing priorities of urbanites nation-wide, newly oriented toward more ecologically diverse experience in the urban environment. The newly designed and built artifacts and architectural elements are bringing us into closer contact with lost ecological systems, habitats and wilderness, and are sheltering us from the effects of the automobile. Through their re-design, sidewalks, streets and parking areas are being reclaimed as places for water, plants, birds, insects and simultaneously, as places for people.

(Parking Day - example of temporary pedestrian appropriation of space typically dedicated to cars.)

To make matters even more complex, the lack or presence of humans on a site becomes a variable to wildlife as well, thus developing reflexive relationships between humans and wildlife.

The city’s open spaces have been developed organically – often shaped by circumstances unique to the era in which they were built. The histories of these sites then record, in part, the history of the city’s development. But a new impetus in public space design which has prioritized returning sites to their states before the settlement of San Francisco inverts the relationship of history and site by using the space of the public site to explore the natural history of the Bay. Since the city was settled so rapidly, it is uncertain what exactly the San Francisco landscape looked like ages ago, or how biotic communities functioned prior to human settlement. Public efforts are returning most of the ecologies studied to their “native” states.

- (Forensic Ecology – Growing interest in the natural history of cities have produced studies showing what cities might have looked like before human settlement. This image shows New York’s Battery Park circa 1700.)

These sites become forensic in nature. They tap into the growing interest in researching the ecological past of what are now dense urban centers. New open space projects that leverage the findings of this research establish connections between the pedestrian and the natural history of the city and provide a new context within which to situate proposed projects that link the various open natural spaces within to city creating new systems or supplementing existing ones. Sites which excavate the natural past for present populations have substantial projective value, and concerted efforts on the part of ecological historians and designers to work together could pay high dividends in enriching urban public spaces and creating more sites where nature may re-establish itself within the confines of the city. This is a theme we have investigated in past projects such as our investigation, “Agri-Structure | Eco-Structure,” and is one that we firmly believe carries great potential.

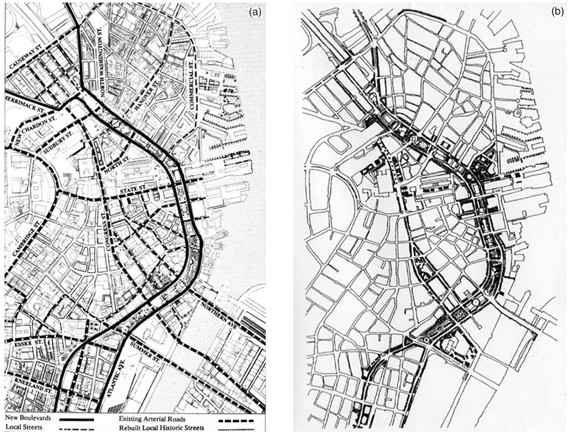

Another dimension relating to the pattern of development of San Francisco’s urban spaces is the organic, piecemeal process in which this network has taken shape. While San Francisco boasts a wide range of scale and size in its public open spaces, these parks, alleys, and pockets of green are most often discrete objects – relationships with other open spaces are either non-existent or have evolved through creative temporary programming often organized in grassroots fashion by city dwellers (take for example, the many small farmers markets that transform otherwise quiet streets between neighborhoods into temporary pedestrian public spaces). This pattern stands in stark contrast to cities such as Boston, which have historical precedents for large public space meta-projects (ie, Olmstead’s Emerald Necklace, and the recently completed Central Artery Project). This is an example of a process that is the polar opposite of the pattern of open space development in San Francisco. However, while these meta-projects laudably attempt to create defined connections between multiple public spaces, the very nature of their planning and construction is disruptive, costly, and time consuming. Despite these inherent drawbacks, their scale also carries visionary portent and suggests a greater city that could leverage its emergent possibility when perceived on the macro scale. We would like to propose such a project.

(Boston's Central Artery - Proposed Open Spaces)

(Re-scripted uses for existing public space questions the necessity of large-scale infrastructural intervention.)

(Pavement to Parks (San Francisco) - An example of small scale public space design as a counterpoint to large-scale infrastructural overhaul.)

Given these precedents, our study’s proposal is for a project has not yet taken shape. This project would combine the discrete nature of San Francisco’s public spaces, the grassroots community involvement of the city’s population, and the vision and foresight of larger infrastructural projects. Could a planned network of temporary and permanent small scale urban spaces that collectively assist in filling the gaps between the city’s existing public urban spaces combine these three strategies successfully? Such a project could breathe new life to under-utilized spaces, find new uses for unnecessary program, and bridge successful sites with each other, creating a new layer of experience within the city. The discrete and small scale nature of each individual project would encourage community involvement and private investment into collective urban spaces. The large-scale vision of the project would ensure that these sites form relationships with existing public spaces, and create a new pedestrian experience within the city – encouraging further investment and community involvement.

We believe that the San Francisco’s goal should be nothing short of being the premiere pedestrian city in the country. A pedestrian open-space network such as we propose would form the basis for a new sense of what a “landmark” project entails – monumental in ambition but without the need for monumental form. To achieve this, we believe that a new metabolism or systemic project that is connected and incremental is necessary, finally evolving into a fulfilled promise for a better pedestrian city.